| Piled Higher & Deeper by Jorge Cham |

www.phdcomics.com

|

|

|

||

|

title:

"Frozen" - originally published

5/7/2014

For the latest news in PHD Comics, CLICK HERE! |

||

[All the content notes and trigger warnings in the world. It's about Game of Thrones, so, you know. —SM]

Express even a modicum of distaste for the extra-rapiness of HBO’s Game of Thrones and you’ll inevitably hear this kind of comment: “But there was plenty of rape in the Middle Ages! It’s realistic! Deal with it!”

The same thing happens if you comment on the show’s sometimes cringe-worthy racial politics: “There were no people of color in Medieval Europe! I’m being realistic! Deal with it!”

Let’s put aside for a moment that the second comment isn’t even close to true. Here’s a thought-experiment for all the realism-referees in the audience. Seven percent of girls and 3% of boys in grades 5-8 in the U.S. report having been sexually assaulted. Do you want to see between 3 and 7% of the kids on TV sexually assaulted?

Don’t you dare say you’d prefer not to. Don’t suggest it might be exploitative or simply cruel. Don’t ask if such scenes are necessary to the story. ’Cause if you do, here’s what I’ll say: Shut up. It’s realistic. Deal with it.

Maybe you think my analogy is unfair. Fine. A less incendiary one: Have you ever watched Girls? Have you ever seen Lena Dunham strip and have sex with people? Have you ever complained about her nudity? Well, you can’t. Women who don’t look like supermodels take off their clothes and have sex all the time. So stop whining. It’s realistic. Deal with it.

What I’m saying is that appeals to realism are not applied across the board. I have no statistics on the matter, but it seems they’re often used to shut down criticism that comes from “haters,” a.k.a. marginalized people who hope to bring attention to TV’s backward politics. But when a show dares offend the sensibilities of a certain type of fanboy, suddenly we’re not talking about realism anymore. Suddenly the conversation is about what “people” do and do not want to see on their screens.

Apparently more offensive than rape.

But appeals to realism aren’t only used to shut down criticism. They’re also used to damn and to praise. This movie is bad because the science is inaccurate. That movie is good because the period details are spot on. This show is bad because the dialogue is heightened. This show is good because there are no plot holes.

It often makes sense to use these arguments. If you’re judging a work of hard sci-fi, it’s reasonable to put a magnifying glass on its technology and physics. If we’re watching a thriller and a plot hole destroys your ability to suspend disbelief, nothing I say is going to make you like the work. Nitpicking TV and movies for fun is Overthinking It‘s raison d’être, so far be it from me to tell you it’s always wrong.

It’s just weird when I enter forums and comment threads about Game of Thrones, and I find myself back in the 1800s, and everyone’s Émile Zola—except this Zola’s applying the rules of naturalism to a story featuring dragons. It’s like everyone got together before the first episode and decided Westeros was a real place and its history real history, and any naysayers are idiots ignorant of the Way Things Were.

It’s bizarre.

It’s equally bizarre when these would-be Zolas apply their rules to works of surrealism. Take those who have burned my dear Hannibal with a dire brand reading “unrealistic.” Unrealistic?! This brazenly surrealistic bit of Grand Guignol?! Why, I never expected this of Bryan Fuller! I’d better renounce my fandom.

When did appeals to realism become a trump card in pop culture criticism? And when did we agree that a certain kind of Internet commenter is the final arbiter of what is real and what is not?

I have some unverifiable theories.

1. Capitalism did it.

Today we’re living in a world where practicality is fetishized and anything dubbed impractical is anathema. You majored in engineering? You’re a hero. You majored in art history? You’re the worst, and you deserve to starve. It’s why half the guys I know say things like, “Oh, I don’t read fiction. I only read Steve Jobs biographies and The Wall Street Journal.” (They might also watch Shark Tank.) In today’s world, fiction is frivolous. Non-fiction is practical and might help you achieve financial success.

In such an environment is it any wonder that we treat works of fiction like clockwork machines and unrealistic elements as broken widgets? When someone criticizes our favorite story, we defend our enjoyment by saying the work is almost as realistic as non-fiction, and therefore it is practical and worthy. I actually met a guy once who justified his enjoyment of 24 by saying it taught him invaluable lessons about how the world really works. No wonder procedurals are so popular. They seem realistic and educational, even when they are not.

Even watching a fantasy like Game of Thrones can be framed as a practical pastime. Though few watch the show to learn to conjure a shadow baby, people do seem to take life lessons from Tywin and Littlefinger, thinking them masters of realpolitik. Act like Tywin or Littlefinger in the office and you might manipulate your way into a promotion, and you can justify your underhandedness by muttering, “In the game of raises, you win or you die.”

2. Lit snobs did it.

Maester Pycelle at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop

Although literary fiction doesn’t have to be realistic, you wouldn’t know it from the literati who decry science fiction and fantasy. We’ve all read a billion articles about how genre fiction sucks—well, unless it’s Latin American, in which case it’s Magic Realism, and the realism part makes it better.

The lit-fic world seems to be slowly changing (thanks, Michael Chabon, et. al) but I doubt my sword-and-sorcery manuscript will be welcomed in an MFA workshop any time soon. You even see this anti-genre snobbery when major outlets discuss YA literature. The dystopias and supernatural romances are raking in the cash, but only John Green’s works of realism get labeled Actual Literature.

So if you want Game of Thrones to snag some literary cred, you have to call it realistic. You say it’s not like those other fantasies with their silly zombies and wizards. Game of Thrones has realistic zombies and wizards, and they’re barely even there! Plus women get raped a lot, so it’s as miserably naturalistic as Zola’s Germinal. And miserable reality is what good art is all about.

3. Sexism did it.

Culturally, feelings and irrationality are considered feminine, while coldness and logic are masculine. Women make things up in their silly little heads, which are clouded by hormones and lady-subjectivity. Men are objective enough to see Reality. This might be why we believe more “realistic” shows (even if they are works of fantasy) are more manly than, and therefore superior to, “unrealistic” shows (even if, like soap operas, they ostensibly take place in the real world).

Since you won’t believe me unless I cite a white guy with a fancy French name, Jacques Derrida backs me up. According to his theory of phallogocentrism, in Western societies, determinateness, which is coded as masculine, is privileged over indeterminateness, which is coded as feminine.

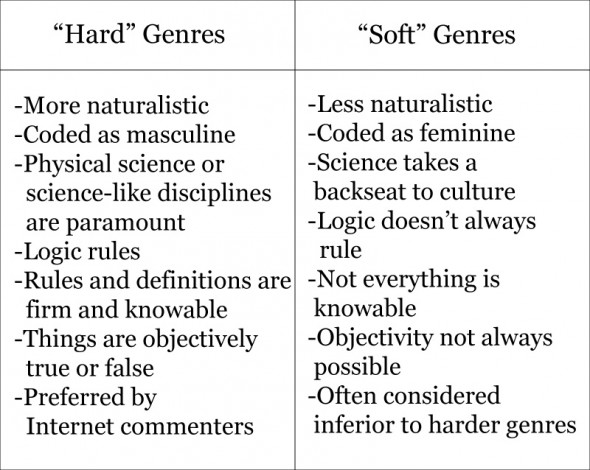

To put it in pop culture terms, it’s kind of like the difference between hard and soft sci-fi. In hard sci-fi, scientific laws and definitions are knowable, logical, clear, and unchanging – determinate. Hard sci-fi is believed to be quite masculine. Soft sci-fi is less scientific (at least, according to our contemporary understanding of science, which might change tomorrow), and it’s more concerned with nebulous concepts like culture. In soft sci-fi there isn’t necessarily one Truth, Reality, or Logic. Definitions and distinctions might be blurred. Soft sci-fi is therefore perceived as less rigorous, girlier, and generally inferior to the hard stuff.

(Side-note: Derrida would say in Western societies everything hard is considered superior to anything soft, because boners. He’d also say the very urge to divide sci-fi into the strict binary of “hard” and “soft” is a symptom of phallologocentrism, which places high value on dichotomies like masculine/feminine, logic/emotion, and science/humanities.)

When it comes to other artistic genres, naturalism is harder, while surrealism is softer. Naturalism is premised on the notion that we can know reality well enough to mime it in our art; the setting of a naturalistic work must be determinate. Though filed in the fantasy TV section of Amazon,Game of Thrones can be considered naturalisticenough, because it is based on real history, and its few, rarely-seen fantastical elements supposedly follow strict, determinable rules. Viewers may not know what those rules are exactly, but we assume they exist. We couldn’t make Game of Thrones RPGs and board games if there weren’t hard and fast rules – a fantasy science, if you will – and these rules make the show more manly and realistic than works of soft SFF or surrealism.

(Personally, I’m not convinced the magic in GoT follows any rules. If there are rules, they seem to be changing. I’m interested to see what viewers say if and when they find out this world is softer than they imagined. Will audiences revolt, as they did at the end of LOST and Battlestar Galactica? I can’t wait to find out.)

George R.R. Martin

The trouble is, these three theories fail to answer an important question: If realism is so admired nowadays, why is no one watching the most realistic shows and movies? With its mumblecorish dialogue, understated acting, racial diversity, and subtle humor, Looking is one of the most naturalistic shows on TV. I don’t know a single other person who watches it. I don’t think I know anyone who’s even heard of it, which is sad. It’s very good.

The documentary-style Friday Night Lights? Canceled. Had to be picked up by DirecTV so it could finish its final season. Parenthood might be coming back next year, but a 1.3 rating in the key demo for its season finale ain’t great. Not when the pulpier Blacklist got a 2.7 and NCIS a 2.5.

As for movies, well, I don’t need to tell you. How many people saw Before Sunset, and how many people saw Captain America? We’re still judging superhero movies based on their realism (a friend recently raved about The Winter Soldier by calling it “barely fantastical—it could happen in real life!”) but when it comes to watching actually-realistic movies about real people dealing with real conflicts in the real world, audiences are nowhere to be found.

So here’s what I want.

I want the Internet to stop pretending it actually cares about realism as a genre. You like dragons and superheroes and pulp. It’s okay. It’s awesome. Own it.

I want people to stop acting like realism is the most important criterion to use when judging pop culture. Character consistency matters, too. Emotions matter. Artistry matters.

I want people to stop applying the rules of naturalism to stories that aren’t trying to be naturalistic. I hate to say you’re watching wrong, but you’re watching wrong.

Most importantly, I want people to stop justifying sexism, racism, and general misanthropy with appeals to realism. We never said we want to see fewer rapes in Game of Thrones because they’re unrealistic, so arguments on these grounds are illogical. And the next time you start to shut a conversation down by saying, “It’s realistic” or “It’s not realistic,” maybe take a second to ask yourself, “So the f*** what?”

To Hell With Your Realism originally appeared on Overthinking It, the site subjecting the popular culture to a level of scrutiny it probably doesn't deserve. [Latest Posts | Podcast (iTunes Link)]

Internett er full av pene, unge kvinner som smiler innbydende mens de forteller at de er feminister: Se min nydelig barberte armhule. Jeg er feminist, men samtidig svært pen. #feministjavisst

Jeg skal gi deg feminist, jeg. Se for deg den feministen du er så redd for å likne på, litt store pupper, vide kjoler som skjuler litt mage, mønster du ikke liker, hår der du ikke har hår, ørepynt som du ikke ville hatt på deg. Hva mer er det å være redd for? Ja, samma. Sånn ser jeg ut. I tillegg sur.

Og du, min unge venn, du kommer også til å se sånn ut når du blir 60. For du kommer mer eller mindre til å beholde den stilen du har nå med ørepynt og hår og klær. Og da, kommer de som er yngre enn deg til å peke. Da er det din tur. For det er ikke form og farge det er noe feil med, det er hvem som bærer det. Uansett hva kvinner over 50 bærer, blir det feil. Dette vil skje deg også, med mindre du ser til satan å bli feminist.

Men så! I mai var det Kristian Tonning-Riises tur til å gå av skaftet fordi noen påpekte det faktum at hans venner i Oslo Freedom Forum har rare sengekamerater. I påpeke slike fakta er "brønnpissing" i følge den ikke utpreget saklige Tonning-Riise. En gjesteskribent på Minerva var mer nøktern og kalt kritikken av OFF for "virkelighetsfjern".

De enda mer liberale kaller det en kampanje mot OFF, mens den nasjonal-konservative Hans Rustad kaller det en heksejakt.

Hva kan vi lære av dette? At høyrevridde kan gå til sengs med hvem de vil? At høyrevridde kan lefle med anti-demokratiske aktører, men likevel kalle det "freedom"? Ja, dersom noen på venstresiden gjør slikt får de Bård Larsen på nakken. Uuuhuu.

Who will bring about political reform, and what are the political incentives for doing it? The question comes from an earlier post. Is there a road-map for exiting from a sub-optimal equilibrium in the way political institutions function? I don’t know the answer.

In Ireland, parties in opposition seem to agree that the lack of accountability of the executive to parliament is a problem. But why would they voluntarily cede the advantages of executive autonomy when in power themselves?

In Greece, the question as to who will introduce real reform is more serious because the problems are so much more pervasive. Behind the massive improvement that has been achieved in the primary fiscal balance, many would still hold that the political system often works badly (inefficiently, ineffectively) and that corruption is a pervasive feature of everyday life. People don’t have much confidence that the institutions of state will act impartially (the keystone of good governance, as Rothstein and Teorell tell us), or even that the rule of law will prevail in the justice system. But individuals can’t change the perverse institutional incentives by themselves. They are stuck with their decidedly dysfunctional political culture, trying to work through it as best they can.

These are problems of different degrees of severity and intractability.

In the Irish example, we could think of it as a problem of time-inconsistent preferences. Governments could bind their own preferences for more power now in order to secure a better outcome later (better-quality policy or better regulation for example). But there will still be specific costs to the reforming actors now, since the immediate change will benefit their political rivals rather than them; and the eventual gains may be uncertain and hard to estimate anyway. We could perhaps imagine a deeply unpopular government that knows it’s heading for opposition status after the next election. It might try to enact political reform now in order to make life in opposition more bearable for itself. But it’s still a tricky calculation.

In the Greek case it’s hard to think where the leverage point might be. Formal and informal institutions interact to sustain mutually reinforcing incentives for suboptimal practices, in ways that Douglass North has helped to make familiar. Bo Rothstein argues that the best option may be a ‘Big Bang’ approach to reform, where everything has to change simultaneously and over a concentrated period of time. The aim would be to change the institutional incentives that shape people’s expectations about how other people will behave.

But we still have the problem of who would take this on and how it would be sustained. In Greece, the economic crisis may have intensified the pain caused by the present system, but it hasn’t noticeably increased political leaders’ commitment to change. Pressure from international agencies, for example in the form of loan conditionality, isn’t directed at institutional reform: budgets, it seems, are ‘technical’ matters, while bureaucratic practices are ‘political’. And the time-frame is likely to be challenging, say between ten and twenty years – short in historical perspective, but spanning several electoral cycles.

So it seems we’re back to piecemeal reform. I’m less pessimistic about this than Rothstein seems to be, if we think of it in sectoral terms. It’s probably a lot easier to get a new set of priorities going amongst the top cadre in some key institutions than across the whole political system. I’m thinking of, for example, the tax administration, or the courts service – agencies that can be given operational autonomy from political interference, and in which new sets of incentives can be set up and protected throughout changes of government. It’s the kind of ‘middle-range’ reform practice where expert assistance from international agencies may well be useful. Self-reinforcing ideas about professional best practice might well become institutionalized (see for example the Center for Excellence in Finance in the Balkans), and policy diffusion could then make a real difference. Or so we may hope.

So much of the discourse around the US and genocide focuses on the sin of omission, the failure of the US to prevent or stop genocide elsewhere. Now that former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt has been found guilty of genocide and sentenced to 80 years in prison—a fact established by a UN truth commission in 1997 but often ignored in the literature on genocide and intervention, which tends to focus on Rwanda and Bosnia—perhaps we can attend to the sin of commission. For the US support for Rios Montt was extensive. I wrote about just a little of it in the London Review of Books in 2004:

On 5 December 1982, Ronald Reagan met the Guatemalan president, Efraín Ríos Montt, in Honduras. It was a useful meeting for Reagan. ‘Well, I learned a lot,’ he told reporters on Air Force One. ‘You’d be surprised. They’re all individual countries.’ It was also a useful meeting for Ríos Montt. Reagan declared him ‘a man of great personal integrity . . . totally dedicated to democracy’, and claimed that the Guatemalan strongman was getting ‘a bum rap’ from human rights organisations for his military’s campaign against leftist guerrillas. The next day, one of Guatemala’s elite platoons entered a jungle village called Las Dos Erres and killed 162 of its inhabitants, 67 of them children. Soldiers grabbed babies and toddlers by their legs, swung them in the air, and smashed their heads against a wall. Older children and adults were forced to kneel at the edge of a well, where a single blow from a sledgehammer sent them plummeting below. The platoon then raped a selection of women and girls it had saved for last, pummelling their stomachs in order to force the pregnant among them to miscarry. They tossed the women into the well and filled it with dirt, burying an unlucky few alive. The only traces of the bodies later visitors would find were blood on the walls and placentas and umbilical cords on the ground.